Poetry Pie (Mar. 30) - Sonnets

Your weekly slice of Poetry

> Shakespeare

> George Herbert

> Gerard Manley Hopkins

This week of Poetry Pie features... sonnets! The most popular form used in English poetry, the sonnet has been in use since the earliest times of the English language (as we now use it). This form was translated into English in the 1500's from the poetry of Petrarch, an Italian man who has some of the credit for perfecting and establishing the form. It took on further development, most notably by Shakespeare who wrote over 150 of them. Though the form was originally used exclusively for romantic poetry, John Donne was one of the firsts to use it for religious purposes, which he exemplified in his "Holy Sonnets." Since then, the form has been used for just about any theme imaginable.

The sonnet is classically composed in 14 lines of iambic pentameter. It is split into a section of 8 lines (octet) and then a section of 6 lines (sestet). Its rhyme scheme varies slightly, but will usually have any of the following sequences:

- ABBA ABBA CDECDE

- ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

Perhaps one of the reasons why the sonnet has been so popular is that they are neither too short nor too long. They are the perfect length for exploring an idea without over-explaining or exhausting the poetic ideas. Some have even suggested that the ratio of octet to the sestet (8 to 6) is a pleasing ratio, one that mirrors the ratios of the human face.

Before we jump into the sonnets below, it's important to note that the sonnet will often have a turn at some point within it. This turn will be a point when the mood changes, or when a solution arises to the problem that has been raised. Many times, this will happen between the octet and the sestet, but it can also happen later. So, as you are reading, look out for the point when the poem "turns" and a conclusion is approached. Enjoy!

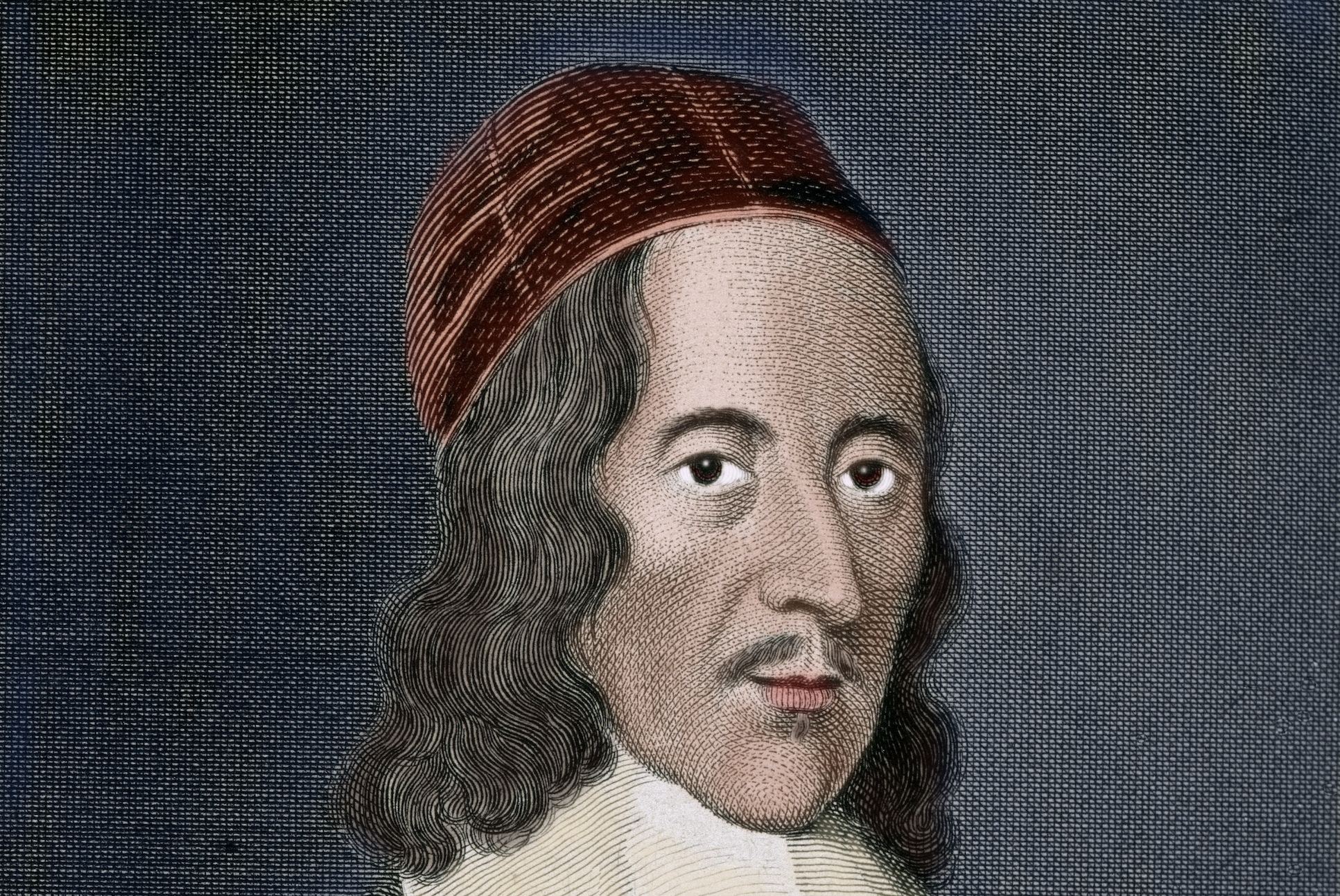

Sonnet 29

William Shakespeare (1564—1616)

This sonnet is a perfect example of both Shakespeare's style and the general structure of what many sonnets do. Notice how the first octet is very downward focused: he is lamenting his poverty and lack of prestige. Heaven is deaf to his cries, he has no friends, and he is envious of those around him. But see what happens on the ninth line (the start of the sestet). It begins with the about-face of a "Yet" as he changes his focus to "thee" who loves him. Suddenly, all of those things that he was bemoaning disappear, the scales are reversed, and he considers himself wealthier than kings.

One signature of a Shakespearean sonnet is the "couplet" at the end (the last two lines that rhyme with each other.) Shakespeare was a master at these endings, concluding the sonnet with a witty turn or a punchy statement. Part of the power of these lines comes from the fact that they are rhymed back-to-back. The rest of the rhymes in the sonnet are split apart by at least two lines, but this couplet is very clearly heard, further accentuating the power of the conclusion. If you're interested, read more Shakespearean sonnets and see how they have similar patterns.

Love (II)

George Herbert (1593—1633)

While I could have included one of Donne's "Holy Sonnets" in this week's Pie, I decided to select one from one of his contemporaries, who was influenced in some way by Donne. "Love (II)" is the poem that proceeds (as you would imagine) "Love (III)," a poem that is quite meaningful to me, from which I took the title of my blog. Both Love (I) and (II) are religiously themed sonnets.

Those familiar with the "Love (III)" will recognize familiar language in this sonnet. There are themes of God pursuing us with his flames, refining us to desire him and burning away our lusts. The ending line leads perfectly into "Love (III)" as it references "Him Who did make and mend our eyes."

Having only ever read "Love (III)," I'm curious now to see how all three of these poems work together. The first two are sonnets in which the speaker is discussing matters of God. But (III) is different in that it is not a "telling" but rather a "showing" of the love of God. Read these other two poems yourself and note the developments between them.

God's Grandeur

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844—1889)

I have lately been growing in my enjoyment of Hopkins' poetry. He wrote many poems that are shaped as sonnets, yet he doesn't retain the same rigid meter as do the older poets. This gives the poem a more natural feel to it, allowing them to pick up momentum in certain locations and slack off in others.

This sonnet is a nature poem, describing the limitless life found in nature compared to the dreary decay brought on by the industry of man. It is very similar to the famous nature sonnet by Wordsworth, called The World Is Too Much With Us, yet it is different in significant ways. This poem is not in vein with modern environmentalist ideas, where Nature (capital N) is some independent entity that is to be preserved over and above the needs of mankind. Rather:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God

"Charged" here has almost a two-fold meaning. It is charged with the task of revealing the grandeur of the One who made it. But also, it is charged (just as we charge our phones) with the energy and glory that comes from God. As such, it can never be exhausted.

The key to all of this is found in the profoundly beautiful ending. Yes, mankind distorts and misuses nature, spending it for his own industry. Yet each new day begins with the Holy Spirit "brooding" over it, eager to fill it with new life and work it for his glory. It often seems as if the environmentalists would like to kill off mankind for the sake of nature. God rather redeems and restores man such that nature can truly flourish under his stewardship.

(I must continue on, but the dramatic sunrise in this poem makes me think about the scene in "The Return of the King," when Rohan is riding to rescue their brothers in the Battle of Pelennor Fields. They arrive and are filled with dismay at the blackness of the sky - a work of Sauron - and the destruction that Mordor has brought to Gondor. But then, the sun breaks over the horizon and King Théoden rallies his men with a speech that I inexplicably can't read without tears:

Arise now, arise, Riders of Théoden! Dire deeds awake: dark is it eastward. Let horse be bridled, horn be sounded! Forth Eorlingas! Arise, arise, Riders of Théoden! Fell deeds awake: fire and slaughter! Spear shall be shaken, shield be splintered, a sword-day, a red day, ere the sun rises! Ride now, ride now! Ride to Gondor!

Pour Me Life

Abram Newcomer

Though I have written a number of sonnets through the years, it seems fitting for me to include the first that I ever wrote. I attempted my own "innovation" on the sonnet form by repeating the rhyme scheme of ABBA until the final couplet. The poem is a prayer of repentance to "Abba" (an allusion to the rhyme scheme), a plea for Him to spare me from his wrath and change me for his glory.

I hope you enjoyed this week's discussion on sonnets! Most of all, I hope that this has encouraged you to read more of them, understanding more about the most famous form in English poetry. Have a good two weeks until the next edition of Poetry Pie!

Discussion